By all accounts, the Nationals had a good draft. In the part that really matters — Day 1, which is composed of the first two rounds — they did what has worked so well for them in the past: Pick players (usually pitchers) who fall for reasons other than ability. The selections of lefty Seth Romero and righty Wil Crowe meet those criteria to a T, as Romero fell due to character concerns and Crowe fell due to medical concerns after his return from Tommy John surgery. In the part that matters least — Day 3, which is rounds 11-40 — they did what every team does: Select enough players to fill out your minor league teams, with a few unsignable high schoolers and your executives’ grandkids thrown in.

But in the middle area of Day 2, or rounds 3-10, the Nationals’ approach was curious. Major leaguers often come from this range, though it’s much more of a crapshoot than the first day. In an unusual move, they spent seven of their eight picks on pitchers. That made for nine pitchers in the first 10 rounds — where the majority of the major leaguers in a given draft come from. By contrast, they chose just three pitchers with 11 picks in rounds 1-10 last year. They picked six and five pitchers in the first 10 rounds in 2015 and 2014, respectively.

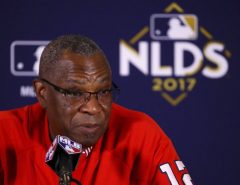

It’s easy to see this imbalance as simply a consequence of how the board fell. Mike Rizzo set that interpretation up nicely in his predraft press conference, saying, “We feel it’s a very pitching orientated draft. College bats are kind of at a minimum, so if you want one of those you have to reach up and get it. … We see pitching as the surplus in the draft, and it’s a deep draft this year.”

As if to drive the point home, Rizzo signaled that he wasn’t concerned about adding pitching to the system after it took a hit with the Adam Eaton trade, saying, “We rarely go for organizational need. We try to get the best, most impactful player in each particular round, because our philosophy is if you have good impactful players, that can get you any kind of player that you want in the trade market. We’re going to identify what we feel gives us the best and most impact in the draft and just take it as each round comes.”

Perhaps Rizzo, ever subtle, was trying to signal that the team would be looking primarily at pitching without acknowledging a weakness in the system. Whether or not that’s true, scouting director Kris Kline blew up his GM’s spot after Day 2, saying, “We wanted to fortify our system with pitching. That was the goal going in.”

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with pursuing pitching in the draft. The Nats had an acute need for it, not only to compensate for the Eaton trade losses but also to fill out the short-season rosters that are already full of hitters from last summer’s international signing bonanza. But my quibble with the Nats’ draft strategy lies in what type of pitchers they chose.

Third rounder Nick Raquet, sixth rounder Kyle Johnston, seventh rounder Jackson Tetreault, and eighth rounder Jared Brasher have quite similar scouting reports in one respect: They all have dynamite raw stuff but have trouble locating it. Even the Nats’ 15th round pick, Bryce Montes de Oca — a third round talent who will require a big bonus to sign if he does — fits the bill. That type of profile screams two words: Future reliever. That future may even be now, as Kline implied the Nationals would put Raquet in the bullpen immediately and Brasher spent time as a reliever last season. Given the big-league bullpen’s current struggles, did the Nationals put a particular emphasis on future relief prospects?

A caveat: The picks in rounds 3-10 often don’t reflect who the team had at the top of its board. Teams will often draft players who will sign for cheap in those rounds in order to save their bonus money for other, riskier shots. But of all the players to skimp with, the Nationals chose relievers.

Developing relievers is an inexact science. Unlike starting pitchers or hitters, it’s not as common to see a player drafted, developed, and debut as a reliever. Many major league relievers are failed starters, like Andrew Miller or Dellin Betances. Hell, Kenley Jansen was a catcher, so it’s not exactly a knock on the Nationals that their system is not bursting with viable relief arms. The two most notable non-40-man relievers not named Erick Fedde are probably… Wander Suero and Ryan Brinley? The fact that you’ve never heard those names proves my point.

But perhaps the Nationals want to change that. They found smashing success with their choice of Koda Glover in the eighth round in 2015, so maybe they placed a greater emphasis on finding more Kodas. And frankly, they’re not missing out on much by eschewing a traditional board: The only 3rd-10th round Nats picks from 2012-2014 to make the majors are Nick Pivetta and Spencer Kieboom (though Austin Voth is on the 40-man and Drew Ward is still on his way).

As a staunch anti-reactionary (except when it comes to any prospect doing anything), I would caution against overhauling a draft strategy over a current major league weakness. But in the course of writing this article, I came around on the strategy. Powerful but flawed arms are a better bet to hit the majors than your usual eighth round pick, a scrappy middle infielder who signed for $5,000 and who you’ll release in a year.

This is more of a hunch than a firm conclusion, but it seems that pitchers are more volatile than hitters, and I’d bet that more MLB pitchers come from the draft’s later rounds than do hitters. A quick anecdotal check: 10 players in rounds 6-10 of the 2010 draft have accumulated at least 1 WAR. Seven are pitchers, including Ken Giles, Kyle Hendricks, and Blake Treinen. You’re not going to find your starting third baseman in round 8. Why not see if you can find your setup man? The Nats already have once.

Tags: Bryce Montes de Oca, Jackson Tetreault, Jared Brasher, Koda Glover, Kris Kline, Kyle Johnston, Mike Rizzo, MLB Draft, MLB Draft 2017, Nationals, Nats, Nick Raquet, Seth Romero, Washington Nationals, Wil Crowe

Leave a Reply