As has been mentioned in every single article about the Nationals for the past four weeks, their bullpen is bad. But for once, this is an article that isn’t (directly) about them.

NL pitches per start, top 5:

1. Roark, WAS

2. Scherzer, WAS

3. Lester, CHC

4. Gonzalez, WAS

5. Strasburg, WAS#BullpenIssues #Nats— Eddie Matz (@ESPNeddiematz) May 22, 2017

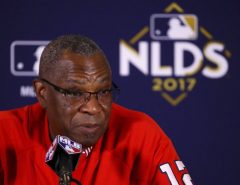

The above tweet made the rounds yesterday, a quantitative manifestation of the bullpen’s struggles and manager Dusty Baker’s mistrust of his relief corps. Those numbers are no surprise; the trend has been visible for some time, culminating in a 118-pitch outing for the notoriously fragile Stephen Strasburg.

But what does ranking so high in pitches thrown mean for a pitcher? I looked at some past comparables to see what this early workload means for the future of the Nats’ rotation.

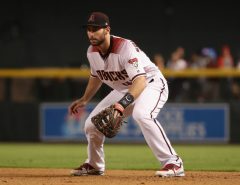

The two easiest pitchers to answer this for are Max Scherzer and Tanner Roark. They ranked second and third, respectively, in most pitches thrown among NL starters last year. The two are simply workhorses: Roark has never been placed on the disabled list, and his stocky frame can withstand the brunt of thousands of pitches better than most. Add in the fact that he didn’t make his MLB debut until he was 26 and that he was a reliever in 2013 and 2015, and Roark is well-positioned to deal with a high-stress workload.

Scherzer is a less obviously durable pitcher, with his high-octane stuff and max-effort delivery making injury feel like a constant risk. But he has only hit the disabled list once, in 2009 — he was placed on it with a sore shoulder on Opening Day but returned just 9 days later. He is meticulous about taking care of his body and ensuring his mechanics remain in the balance that has helped him stay in peak form for so long. He has been in the top 12 by pitches thrown in the majors every year since 2013, and while catastrophists may insist all that wear will catch up to him eventually, he has yet to show any signs of wearing down.

The explanation for Gio Gonzalez’s presence on the list is similar, but includes an additional step. Like Scherzer and Roark, he has been supremely healthy, with a month-long absence in 2014 for a sore shoulder marking his only DL trip in his decade-long MLB career. With the exception of that year, Gonzalez has thrown at least 175 innings every year since 2010, and threw at least 195 annually from 2010-2013.

But despite making his usual full complement of starts, Gonzalez’s innings counts have fallen below 180 in 2015 and 2016. It’s not hard to see why: His walk and strikeout rates are similar, but his hits per nine innings rates went from below 8 in 2013-14 to over 9 in 2015-16. That led to a higher WHIP (1.228 in 2013-14, 1.382 in 2015-16), which meant he would have to contend with more baserunners and throw more pitches each inning, shortening his starts. Throw in the fact that his reduced effectiveness would get him pulled from starts more quickly, and Gio’s low innings totals make sense. But even throwing 177 1/3 innings last year, Gonzalez still came in 10th in the NL in pitches thrown — just behind Jake Arrieta, who threw 20 more innings.

By pitching-independent metrics, Gonzalez’s 2017 has been his worst season ever. He is walking batters at his greatest rate since 2009, and striking out the fewest he ever has. But a high strand rate has given him a low ERA and therefore superficial success. That, combined with the Nats’ miserable bullpen, has him throwing almost three-quarters of an inning more per start than he did last season. That explains why he’s throwing pitches at a higher rate than ever before this season, but his track record shows he can handle throwing a high number of pitches.

This brings us to Strasburg. He has made seven trips to the disabled list since his 2010 debut, which does not his scary arm injury last September. A heavy workload isn’t totally unprecedented or unsustainable for him, as he threw the ninth-most pitches in the NL en route to the league strikeouts lead in 2014. It’s not as though throwing a lot of pitches is a recipe for immediate disaster for Strasburg. He didn’t wear down in 2014 either, posting a 1.13 ERA over his last five starts in 2014 — his best ERA in any five-start stretch that year. But he’s suffered five major injuries in the two seasons since then, so it’s fair to question whether he can maintain throwing so many pitches.

What causes and prevents injury in pitchers is poorly understood; just read Jeff Passan’s The Arm if you want an idea of how poorly. But it should be relatively uncontroversial to say that a higher pitch count for a historically injured pitcher will increase the risk of future injury. On the other hand, Strasburg’s 2014 should show that a heavy workload will not necessarily hurt him in the near term. His struggles since then suggest throwing a ton of pitches is unwise for him, which I’m confident few would disagree with.

Baker was famous for riding his starters into the ground in Chicago, San Francisco, and Cincinnati. With his miserable bullpen, he’s had to return to his old ways in Washington. But Scherzer, Roark, and Gonzalez have all shown they can handle such workloads without eroding their performance or risking injury. Strasburg has shown he can also handle a full season’s workload without running out of gas, but with his injury history, it will always feel wise to err on the side of caution with him.

The starters throwing a boatload of pitches is far from ideal, but history tells us it isn’t unprecedented or even particularly risky. Let’s just hope Dusty eases off Strasburg for a bit, just in case.

Tags: Gio Gonzalez, Max Scherzer, Nationals, Nats, Stephen Strasburg, Tanner Roark, Washington Nationals

Leave a Reply